When you’re looking to tell captivating stories that fully engage everyone at the D&D table, it’s best to look to the masters.

Whether we’re talking about the page, stage, or the big screen, there is no shortage of inspiration out there to pull from.

But today I want to talk about one of my personal favorites.

In his time (and to be honest, even today), he was viewed as a tortured madman. But his theories and unique style of storytelling and stagecraft have gone on to inspire countless productions and shaped our idea of what storytelling even is!

Pulling inspiration from these powerful ideas and applying them to your own game is an excellent way to keep your players hooked.

This is what every Dungeon Master can learn from the visionary creative genius, Antonin Artaud.

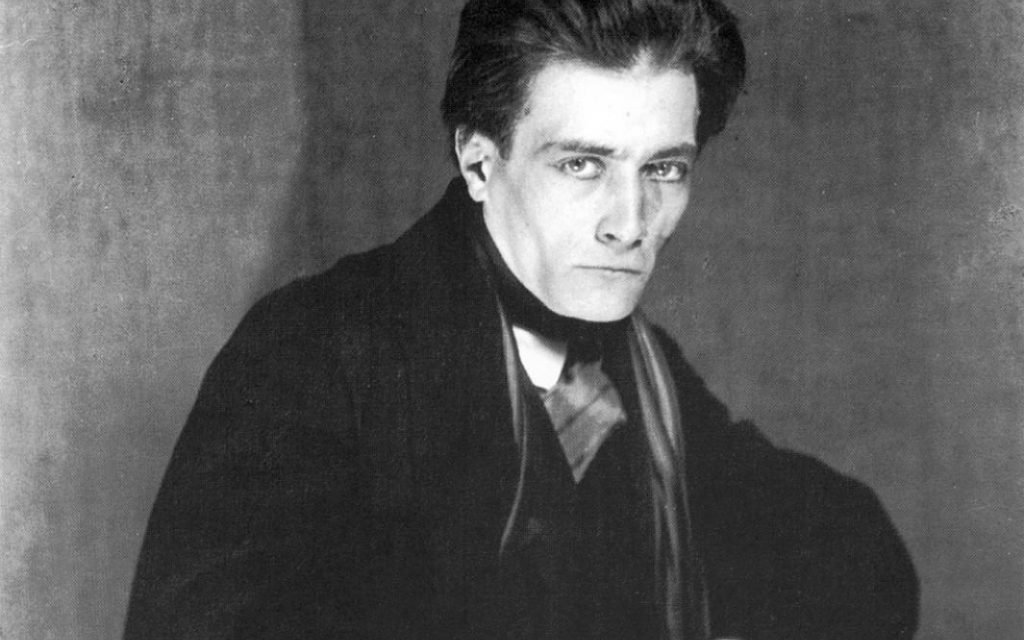

Who Was Antonin Artaud?

Let’s start at square one with who Artaud was.

Antonin Artaud was a French writer, artist, actor, and director in the early 1900s. His creative work is among the most important of the European avant-garde movements of the time and was known for its bizarre and shockingly raw surrealist themes.

Diagnosed with meningitis at a young age, illness (both physical and mental) would be a recurring theme throughout his life.

In fact, a large amount of Artaud’s life (somewhere around 15 of his 51 years) would be spent in various hospitals and institutions. (Remember: this is a time when prescriptions of opium and electroshock therapy were common despite them ultimately doing more harm than good.)

Nevertheless, Artaud worked tirelessly to redefine the theatre and the meaning and methods of storytelling.

He envisioned using theatre as a way to communicate raw and complex emotions in a way that was very real, raw, and present.

This “Theatre of Cruelty” as he would call it, pulled a great deal of inspiration from Balinese dance and Oriental Theatre. These art forms placed the audience squarely in the middle of what was happening and traditionally incorporated deep themes and complex stories.

With almost overwhelming lighting, special effects, and a heavy focus on symbology, Artaud envisioned this Theatre of Cruelty as something that must be truly felt to be understood. His goal was to engage with the audience’s senses and not just their mind through words.

While many of his contemporaries wanted to make theatre as close to real life as possible, Artaud instead saw power in myth and metaphor. In his mind, the goal was to remove as much reality as possible from what was being shown.

However, where many saw a madman, history would eventually smile on Artaud’s genius.

From the stage and the early days of cinema to the modern age of Hollywood and Netflix, Artaud’s influence has reached beyond even just theatre and inspired countless visionaries and creatives.

Antonin Artaud’s Big Ideas

Now that we’ve covered who Antonin Artaud was and his influence, let’s move on to his big ideas.

We’ll start by going over his main ideas as he explained them and how they manifested themselves in his work. From there, we’ll come back and put it all together in a way that makes sense at the D&D table.

Artaud had a lot of truly brilliant ideas, but we can really distill them down to three main pillars. At least for our purposes here!

Recommended: The Best Books EVERY DM Needs To Read

Embrace Surrealism, Abolish Reality

The more realistic the theatre aimed to be; the more boring Artaud found it.

To him, there was a great potential to unleash true magic that was being completely wasted here. The focus on a production being understood, in his opinion, made it impossible for it to have a true impact.

Instead of an audience having lines read to them, he envisioned a production that assaults the audience’s senses so that they stop engaging with their mind and instead engage with the feelings being created within them.

Artaud felt that good theatre is meant to seem more “real” by working as an escape from boring day-to-day life.

In much the same way that you might describe a dream (or nightmare) that makes no logical sense but still deeply affected you, Artaud wanted to capture that.

If you’re taking Artaud’s advice, stop trying to make things as real and “believable” as possible.

Whether we’re talking about a play, movie, or D&D game, being able to remove “what makes sense” is an important consideration. Something being interesting or cool is often enough justification for it to exist in its own right!

This is especially common when we’re talking about worldbuilding.

It reminds me of the introduction to one of my favorite strange films: Rubber.

As a film about a killer tire with psychic powers (yes, seriously), I think Artaud might have enjoyed it. The opening would fit right alongside most of Artaud’s writing and reflections.

I’ll include the video below.

The Power of Myth, Symbols, and Immersion

Artaud insisted that people have a fundamental need for ceremonies and “rituals” in their life. In his view, this is what made the theatre so important.

Costumes should be over the top. Lighting and sound effects should be jarring and intense as if they’re grabbing the audience by the lapels and shaking them awake. Meanwhile, concepts should put emphasis on symbols and what is being represented rather than “what is.”

However, Artaud insisted that there shouldn’t be a focus on props and staging.

Anything that is being used in the performance should be used to further enable the actors to open up from a place of pure emotion in a way that is both physical and sensational.

What matters most is the specific feelings that are being communicated by the actors and being felt by the audience. To this end, Artaud specifically called for “organized anarchy” as the play surrounds the audience who are seated in the center of it.

The focus is not on words and dialogue, but instead on movement, gestures/expressions, and the use of space.

Funny enough, this is not a radical departure from what D&D already is!

In fact, I think “organized anarchy” is probably a pretty good way to describe the standard D&D experience!

Symbols, myth, and over-the-top descriptions/encounters are important parts of what makes D&D the game that it is. Players are both the actors and audience in a D&D session which actually amplifies the power myth and symbols because they can be fully interacted with within the game.

Antonin Artaud passed away decades before D&D would ever be a thing, but I can’t help but think that he would have loved the game!

Related: The Red Thread For Dungeon Masters

The Theatre of Cruelty

But Artaud’s biggest idea (which we’ve already briefly mentioned) is what he called The Theatre of Cruelty.

The other ideas we’ve covered are meant to build into this concept. However, we need to look past the “shock factor” of the name to see what Artaud is really calling for.

“Cruelty is appetite for life, cosmic rigor, implacable necessity. I used the word cruelty as I might have said life or necessity. Fate leaves no room for choices, but necessity does. Not in the sense that we are free to accept it or reject it… but in the sense that we are free to accept or reject ourselves in it.”

-Antonin Artaud

To Artaud, the power of the Theatre of Cruelty was in communicating emotions and concepts in their truest form.

It was going beyond what words are able to describe and portray to communicate directly with the audience’s heart and not their mind.

It’s about creating the situation and message while then inviting the audience to immerse themselves in what is happening through the use of symbols and staging.

Artaud called for less focus on narrative and a full focus on the spectacle and sensations. Bizarre lighting, music, dancing, sound, and other effects were used to fully capture the audience’s attention.

The goal was to create something so radically different and overwhelming to the logical part of the brain that then works as a kind of fun-house mirror to “reality”.

The driving idea behind this is that this portrays a type of “fully realized” version of both life and reality.

By amplifying the spectacle and emotions, Artaud believed that we’re able to strip away the illusions of theatre and of our day-to-day life. From there, we reach something more true, timeless, and “real” in both the play and in ourselves.

To Artaud, good theatre should be more “real” than everyday life.

In other words, he was big on escapism.

How Can Dungeon Masters Use Artaud’s Ideas?

So, let’s now put it all together and consider how this applies to D&D.

Be mindful that these aren’t techniques to be used constantly and in every single situation that arises in your game. View it more as a set of tools that you can use in those situations that demand drama, immersion, and intensity.

As interesting as a D&D game that was “all Theatre of Cruelty, all the time” might be, the real power of this technique lies in dialing up the drama and atmosphere of a specific moment to its absolute highest level.

If you try to apply this to every situation from boss fights to ordering an ale at the tavern, it takes away the impact.

So use these techniques when they’re going to be the most impactful!

Related: What DMs Can Learn From Quentin Tarantino

Feeling Over Logic

What Artaud was specifically trying to achieve with his Theatre of Cruelty was full immersion for the audience. He wanted them to stop thinking logically and to instead understand what was happening through feeling it.

Beyond the lighting, music, and noise was a core message or theme that was being communicated. But to bring that out the thinking/logical side of the audience had to be shut down if they were to “buy in” to what was being presented.

This isn’t so different from a DM attempting to increase immersion in their own games.

The DM creates the vehicle and situations for players to immerse themselves in the game world, but it is still ultimately up to the players to accept or reject that.

If a player rejects that immersion, Artaud would likely insist that the DM would need to increase the spectacle until the player accepts the immersion.

Are they still thinking too logically? Have they been given powerful enough symbols and themes to interact with?

I’m not sure about forcing/overwhelming players into immersing in the game, though it can still signal that the DM can be including more opportunities for immersion.

Description and Emotion

As the DM, you need to paint the picture for your players. It’s not enough to say “a red dragon is attacking.”

Using vivid and guiding descriptions, the DM should paint the chaos being caused by the dragon attack.

But don’t just describe what’s happening or what things look like. You want your descriptions to create an emotional response and not just function as data.

Ask yourself what emotions are associated with a dragon attacking the city and how you can bring those out in the players.

If you can stir those feelings of fear or desperation, the situation becomes more real and the players will be more immersed in what is happening.

Use symbology such as the dragon destroying a huge statue of the city’s legendary hero to represent the scale of this new threat. Even this legendary hero of old is just dust compared to the attacking dragon.

As the temple of a local deity crumbles and burns, has that deity abandoned the city? Perhaps the head priest (who is usually calm and collected) is screaming “The end is upon us! We’re doomed!” and causing yet more panic.

If possible, tailor these “emotion-oriented descriptions” to the characters.

Not only is a dragon attacking, but symbols of what their character holds closest (the hero statue might hold special meaning to a Paladin or Fighter, the temple for a Cleric, etc) are being torn down in the process.

The dragon attack is more of a “logical” situation, but the characters’ responses are informed by the “emotional” situations that surround it which opens a new level of immersion for the players themselves.

People act on emotion and then justify with logic. If you can create that emotional connection, the players will further immerse themselves almost without thinking.

Growth

Finally, we trace back to the very core of Antonin Artaud’s ideas and look at the “why” behind them.

Despite the name of the Theatre of Cruelty, it was ultimately meant to be the kindest and surest way of communicating a feeling of dire importance to others.

As they say, sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind.

While it was almost unbearably intense in the moment, it was a necessary step towards revealing some ultimate truth, message, or opportunity for growth.

But this is where the true power of bringing Artaud’s ideas into your D&D game lies.

When you’ve gotten them to engage emotionally with the story and fully immerse themselves, you’re creating that very tension and “necessity” that Artaud spoke of. When the moment ends, however, you can’t just leave that tension there and you also can’t just turn it off like flipping a switch.

Use the same emotional descriptions that you used to create the drama as a way to bring resolution to it. Where there was once fear, dread, and confusion you should speak to feelings of triumph and relief.

As the dust settles, how is this a growing moment for the characters?

The players will have formed their own emotional connection to what happened. As the DM, you want to reinforce that connection as a way to help the player further explore/develop their character while also rewarding that deeper level of immersion.

This is what creates the epic stories and moments that you and your group will remember fondly for the rest of your lives. It’s that point of growth that goes even beyond the game itself.

Maybe you didn’t really (as in “in real life”) just slay a dragon…

But then again…

…you did.

Conclusion – Antonin Artaud for DMs

The myth of “the tortured artist” is one that most people are well familiar with.

Few have ever been as ridiculed and misunderstood (yet also so very visionary) as Antonin Artaud was. Without Artaud and the influence he had on the theatre, it’s difficult to imagine just how different things like film and, yes, even the theatre of the mind within D&D would be!

But I’m not going to sugarcoat it: Artaud’s work isn’t exactly the most accessible stuff out there.

If this article does inspire you to dig into Artaud’s work, be prepared for some of the most disturbing (but also mesmerizing) imagery and situations your mind could ever conjure up. You’ve been warned.

For most DMs, I think learning these key principles of Artaud’s work is enough. However, it’s such a pivotal way to take the magic that this misunderstood genius sought to bring to the stage and give it a new life at the D&D table.

I hope this article has given you inspiration to try something new and bring more drama to your game!

Truth be told, this is an article that I’ve been wanting to write for over a year now. So, I’m very happy to be able to share it with you now!

If you’d like more articles that pull from the stage and screen to inspire your D&D game, let me know in the comments!

Don’t forget to sign up for the Tabletop Joab newsletter! It’s the best way to get all the latest player guides, DM Tips, news, reviews, and more for D&D 5e right to your inbox!

You can also follow Tabletop Joab on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found this article helpful and want to support the site, you can buy me a coffee here! (It’s not expected, but very appreciated!)